By Kelly McGreal

It’s difficult to describe the sound inside a maple tree during sapping season. As I listen to a recording of the tree’s interior, I find myself groping for metaphors, searching for comparisons. This is a new sonic experience, and I’m unexpectedly moved. What I hear is at once unfamiliar and familiar.

The recording is part of The Underground Sound Project, created by artist Nikki Lindt in collaboration with the NYC Urban Field Station Collaborative Arts Program, USDA Forest Service, NYC Parks and The Nature of Cities. Lindt recorded subsurface sounds for the project, placing microphones underground, underwater, and within trees. She acknowledges these sounds can seem alien or otherworldly but says that for many listeners, there’s also something recognizable:

“Sound is bound to our emotional inner landscape and yet it is deeply rooted in our awareness of our connection to our surroundings. It also has the power to transport the listener.”

This resonates. Sounds can recall feelings, experiences, and memories; Lindt likens it to the way songs take you back to another period in your life. For me, listening to her recording inside a frozen stream is especially evocative. The sound must be unfamiliar (I’ve never been submerged beneath ice-covered water), yet it reminds me of hearing an ultrasound of my daughter, and I feel as though I’m reliving that experience as I listen to the world of sound within the stream. Somehow, these very different occurrences feel sonically adjacent. After listening, I feel connected to nature in a new way.

CONNECTION & SOUND

For Lindt, cultivating connections to places, nature, and the broader ecosystem is central to her work. Deeply concerned about the climate crisis, she sees her art as part of necessary, collaborative effort to talk about and address environmental issues. In our image-centric era, visuals showing the effects of climate change likely resonate with people. Many of us are moved by haunting imagery of polluted ocean water, hazy cityscapes, and animals impacted by habitat loss. Given this, I wanted to know why she started incorporating sound into her artmaking.

Lindt says she began experimenting with sound recording in 2018 while collaborating with a researcher in the Arctic Circle at the Toolik Field Station in Alaska. She was there to learn about permafrost thaw, see its consequences on the landscape, and collect visual data for a project. Lindt explains, “What I saw when I was on site was much more extreme than I could have imagined. Thawing permafrost leaves many forests with such destabilized forest floors that trees grow at all angles imaginable, and huge football field sized sinkhole-like holes are scattered all over the tundra.”

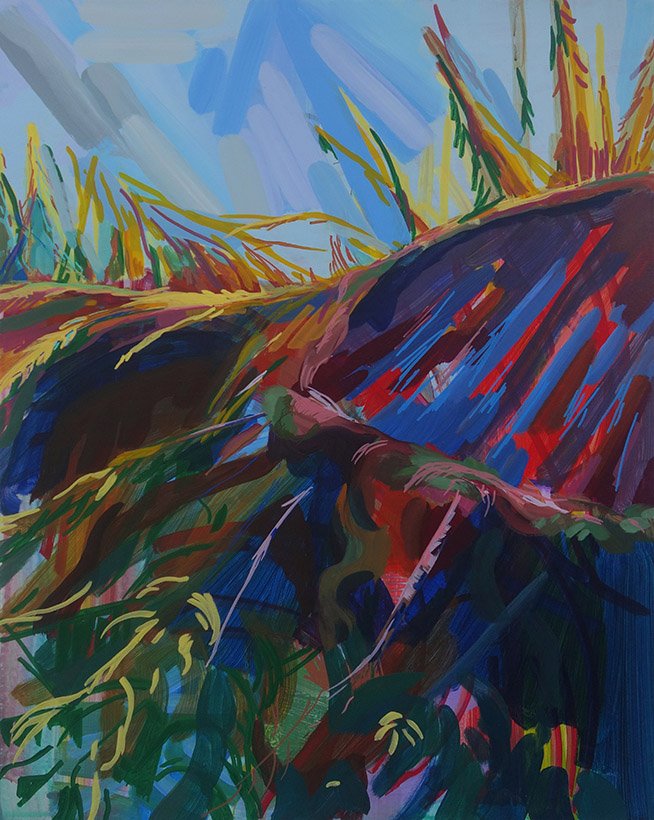

She documented the effects of permafrost thaw on the landscape in her painting series called Tumbling Forests of the North. But the impacts weren’t only visually apparent—she could hear them. Lindt recalls, “While spending time inside those deep sinkholes, called thermokarst slumps, I also started to become keenly aware of the persistent sounds of the thawing permafrost around myself,” noting:

“The sound was peaceful, calming, almost meditative but it was…relentless. It just kept going and going. This duality of such a calming sound paired with the terror of what it represented was deeply impactful.”

She decided to record these sounds the following summer and created an interdisciplinary piece titled Permafrost Thaw, Alaska, Sights and Sound. The work positions a landscape painting (below) depicting the effects of permafrost thaw next to a sound recording. The audio of the persistent thawing transitions back and forth between surface and subterranean sounds. As I listen, I recognize the sound of wet earth dropping, water dripping, water running. At one point, Lindt’s subsurface recording of melting ice inexplicably sounds like burning. In the context of global warming, the effect is sobering.

Lindt says firsthand experience listening to and recording permafrost thaw helped her understand climate change and environmental issues in new ways. “When I later turned to recording subsurface sound in trees, soils, and waters,” she explains, “I realized the power these sounds could have on people’s connection to natural areas.”

I asked Lindt about that connection. I certainly felt it when listening to her sound recordings and wondered if others did, too. They have. She’s had conversations with and read messages from people who have engaged with her work. Lindt has the sense that for many people, being introduced to the hidden, interior world of sound beneath a surface is like learning something new and surprising about a friend. Hearing nature speak in a new way allows listeners to move beyond the surfaces and sounds they’ve grown accustomed to and connect with the entire ecosystem. She hopes people see themselves as part of the broader ecosystem and feel more protective of nature.

LOCATING HOPE

Lindt has been engaging with the effects of climate change in her work for some time. On her website, you can view her Solastalgia series (2012-2018), which explores philosopher Glenn Albrecht’s concept of solastalgia, “a term that describes the feeling of loss of place due to climate change and development.” The series includes a collection of thirty paintings depicting lone figures within natural landscapes. Some appear to be listening to the land or searching for something; others are touching, holding, or reaching for elements within the environment. Sometimes, the figures seem disoriented or unsteady. I find this very moving but also painful.

While recognizing loss, I asked Lindt if she’s found a way to feel hopeful about the possibility of humans mitigating climate change and allowing the planet to recover. She admits, “This has been a long process for me,” saying:

“The fact is that there is a tremendous amount of loss of our natural areas due to housing development and our dependence on fossil fuels and other natural resources. We are not experiencing climate change in an abstract way. It is sometimes very direct and places, experiences, and even weather patterns that we remember are changing all the time. But there are many things that make me hopeful.”

She finds hope in nature. Citing her observations of the brief growing season in the Arctic, Lindt explains, “The insistence of the growth in these short months is palpable. Life is busting out everywhere at a very fast speed. When I experienced feelings of the loss upon seeing the permafrost thaw, I was also confronted by this undeniable life force.”

Just as nature is generative, Lindt sees “the laden potential of collaboration and art” as powerful forces for growth. She regularly collaborates with ecologists, social scientists, land managers, architects, writers, and community organizers whose ideas and efforts inspire and motivate her. Reflecting on her work and process, Lindt says:

“My Solastalgia series was fundamentally about loss. Then, over the years through various inspiring collaborations, my work has built towards connection with the natural world but in a more deeply empathetic way.”

“In The Underground Sound Project, I got to experience landscapes in a new way that brought me closer to them. I wasn’t expecting that, and that act gave me a lot of hope towards a better understanding and cooperation with the interconnected, interdependent ecosystems and communities that we cohabit this planet with.”

AN INVITATION

Lindt invites all of us to deepen our connection to nature through sound. Below, check out her recommendations for listening to nature closely.

KM: Do you have advice for people who don’t have specialized equipment for listening but would like to experience nature’s sounds more deeply?

NL: There is so much you can experience and hear just by taking the time to slow down and by spending time in natural places. This can be in a national forest like Cuyahoga Valley National Park, a local park, or even by an urban street tree. Then give yourself some time to be silent, even if it is just 5 minutes, and close your eyes. Listen closely—you will be surprised by all the sounds you hear. You can also put your ear against a tree and faintly hear some of the sounds I record with my equipment.

KM: You’ve created a soundwalk for The Underground Sound Project in Prospect Park, located in Brooklyn, New York. How can people outside of this area experience your subsurface sound recordings of nature?

NL: You can do the soundwalk remotely by visiting: The Underground Sound Project. When you’re done, consider adding your response to the soundwalk to the response gallery!

Also, if you’re a teacher, check out the learning module NYC Environmental Protection made for NYC public schools and colleges about the Underground Sound Project. Although the module is designed for students living in NYC, it can be adapted for your area. There’s also a section designed for online or in-class learning! Find it HERE.

*ARTIST BIO NARRATIVE

Nikki Lindt is a visual and sound artist living in Brooklyn. Her work focuses on people’s relationship to natural areas, effects of climate change on underground ecosystems (both rural and urban) and environmental awareness. She mostly works in collaboration; with philosophers, ecologists and social scientists (among others) on longer term projects. Lindt has spent time working and collaborating at many field stations including the Toolik Field station in the Arctic, Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest in New Hampshire, the NYC Urban Field Station and the Abisko Field Station in the Swedish Arctic.

She has given many talks about her work and exhibits nationally and internationally. She is represented by Robischon Gallery in Denver, and Heskin Projects in New York City. She has received the Pollack-Krasner Grant, Brooklyn Arts Council Grant, Puffin Foundation Grant, the Dutch Artists Grant (Fonds BKVB) among others and has been awarded the Environmental Cultural Award, Milieudienst (Environmental Protection Agency) Amsterdam, Netherlands.

*Artist’s bio reprinted from Nikki Lindt’s website with permission.