By guest blogger Malinda Moore, Conservancy Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Fellow

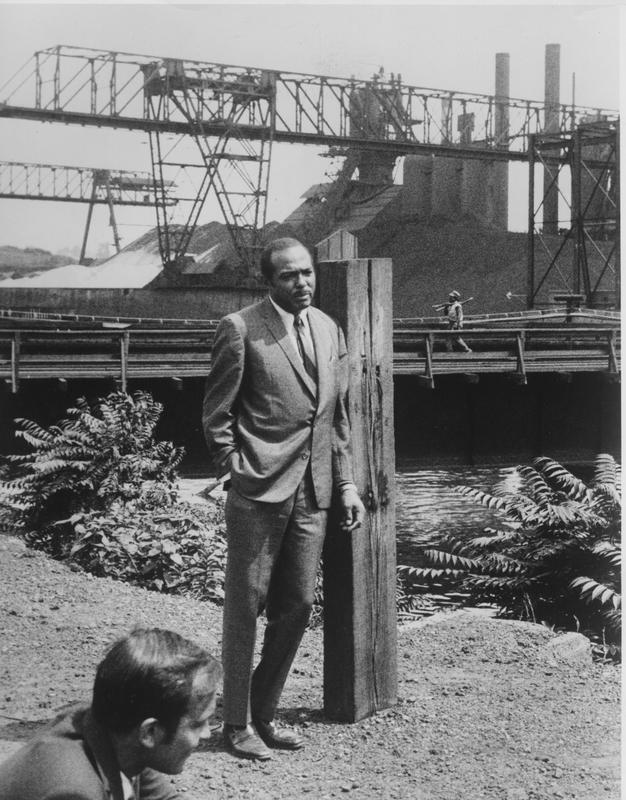

If you’re a Cuyahoga Valley National Park (CVNP) connoisseur, or just a local to the greater Cleveland, Ohio area, the name Carl Stokes should ring a bell. Elected in 1967, Stokes served as this nation’s first African American mayor of a major city when he became the mayor of Cleveland. Nearly two short years later, he was presented with the task of addressing the 1969 Cuyahoga River burning – an unfortunate event that left an undesired spotlight on Cleveland but would become an icon of the environmentalist movement.

We can thank Stokes’ response to the fire for its now infamous status. After the river caught fire on Sunday, June 22, he led a press tour the following Monday. In 2019, environmental enthusiast and residents alike gathered to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the river burning. What everyone seems to remember is that the fire helped to jumpstart the environmental movement in the way of the passage of the Clean Water Act as well as the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency. Despite these well-known advances, it was one of Stokes’ less recognized tactics that continues to have an impact on the fight for issues beyond water and air pollution.

His approach? Addressing what the National Park Service describes as the “urban environment.”

While Stokes made it a point to acknowledge the importance of combating air and water pollution, he also consistently highlighted how these issues disproportionately affected inner-city communities. It wasn’t just the river that was polluted, but the city itself too. Its poorest neighborhoods, rife with dirty air, garbage-strewn streets and unhealthy housing, had also caught fire several times during the long hot summers of the late 1960s.

Stokes was the first to focus on how these issues coincided. What he sparked was not just a movement for environmentalism but environmental justice.

“I am fearful that the priorities on air and water pollution may be at the expense of what the priorities of the country ought to be: proper housing, adequate food and clothing,” Stokes said at the inaugural Earth Day Event in 1970.

Defined by the United States Environmental Protection Agency, environmental justice is the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies. This goal will be achieved when everyone enjoys: the same degree of protection from environmental and health hazards, and equal access to the decision-making process to have a healthy environment in which to live, learn, and work.

It’s a common misconception that Black people are not involved in nature or do not care about the conditions of the environment, when the history of our very existence in this hemisphere includes a deeply rooted connection to the land. No matter how adverse the conditions of that birthing connection may have been, it is a relationship that has continued throughout the years.

Local groups like Green 2.0, Black Environmental Leaders (BEL), Journey On Yonder (JOY) and Black Girls Do Bike continue to knock down the stereotypes and create a new narrative that highlights the African American experience in nature. Here at the Conservancy, our Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion efforts are focused on continuing Stokes legacy of supporting environmental justice while aiding in the efforts to make CVNP a park for all people. I encourage everyone to examine the environmental disparities in your own communities that persist today. As the National Park Service reminds us, part of Stokes’ legacy is to think about how we address issues to benefit us all.

This month, we are highlighting black environmental leaders in our community on our Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. Be on the lookout to hear stories of these incredible people!